Architecture's Response to the Seven Million Homes Shortage

A new report from the National Low Income Housing Coalition warns that the U.S. is short more than 7 million affordable homes for the country's lowest-income renters. For every 100 families in need, only 35 homes are available. It's a gap that not only reshapes cities but also raises a bigger question: what kind of architecture do we need when the numbers are this stark?

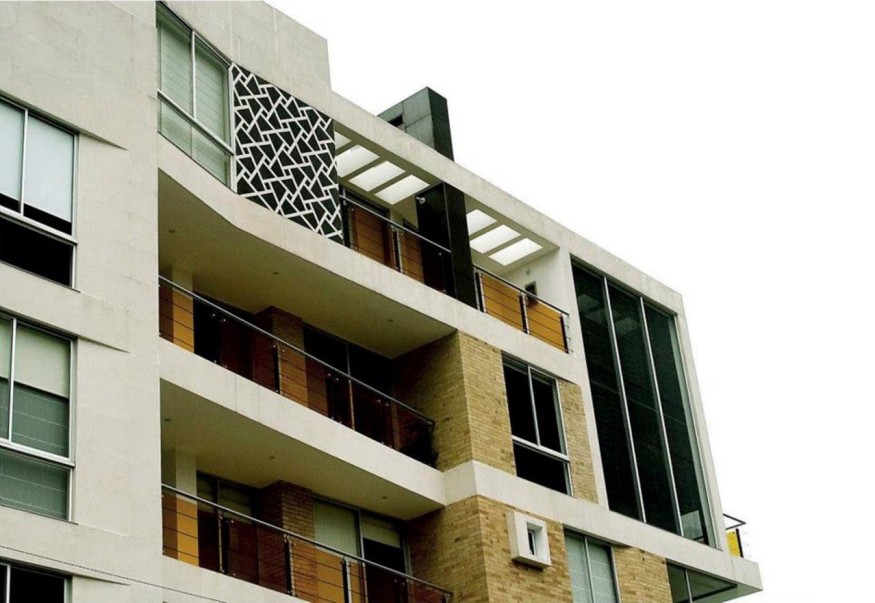

Colombian architect Leonardo Rico Florez, founder and principal of the Studio of Architecture and Building Innovation (SABI), which operates in Colombia and has recently expanded its presence to Miami, knows the answer. He is sure that design must serve both people and investors. With more than 20 years of experience, his portfolio ranges from multifamily housing in Bogotá to the UPTC Engineering Labs in Tunja and institutional remodels for the Agence Française de Développement. His projects have been adopted as references in both Colombia and the U.S., and his design philosophy, that architecture is not a privilege but a right, has shaped a methodology now drawing attention internationally. Through what he calls The SABI Method, Rico Florez blends financial performance with social value, measuring not just returns, but also jobs, accessibility, and community impact. The method works as a replicable model: a set of tools that allows investors to measure traditional ROI alongside social outcomes, giving both numbers equal weight in decision-making.

A New Metric for Architecture

In recent years, architecture and real estate have started borrowing language once reserved for social policy. Terms like impact, inclusion, and well-being now appear in investment reports alongside ROI and yield. The shift reflects a broader reality: buildings are judged not only by how much money they make, but by how they shape the daily lives of those who use them. Investors now ask for greener, fairer projects, while many cities are experimenting with ways to track how new buildings contribute to the quality of life.

Architects and developers are testing different ways to capture less tangible results. Some measure access to public space, others look at jobs generated, or whether mobility in a neighborhood has improved. The SABI Method takes this further by building these indicators into the same equation as financial performance. Instead of treating inclusion or community benefits as side effects, it proposes measuring them from the start—showing how social outcomes can reinforce long-term value.

As Co-Founder and Principal Architect of SABI LLC, Rico Florez defines the conceptual direction and architectural strategy for the firm's projects. Under his leadership, SABI LLC—formerly Rival Arquitectos in Colombia—has delivered around twenty projects totaling over 400,000 square feet across residential, commercial, and institutional typologies. This portfolio includes the 70,000-square-foot UPTC Engineering Laboratories Building in Colombia and the 7,000-square-foot Shanti School in the United States. His strategy of prioritizing design coherence and social purpose has strengthened SABI's standing among institutional clients such as the French Development Agency (AFD) and enabled the firm's expansion into the U.S. market.

As Leonardo explains, "I grew up in a country where inequality was visible in every brick and street. From the beginning of my career, I wanted to prove that good design is not a luxury, but a right. Over time, I saw how design choices could determine both the financial success of a project and the dignity of those who inhabit it, and put those two truths into the same framework." His approach reflects a shift happening across the field that sees success not only in profit margins but also in how architecture supports community life.

Adaptive Reuse Is Having a Moment

One of the clearest signs of this change is the growing interest in adaptive reuse. Across major cities, empty office towers are being turned into housing, old warehouses into cultural venues, and outdated hotels into student residences. The appeal is obvious: it's often faster and cheaper than building from scratch, and it comes with an environmental bonus; reusing what already exists cuts down on construction waste and carbon emissions. In 2025, several U.S. cities even introduced tax breaks to encourage developers to consider reuse before demolition.

For example, in 2025, cities began backing this trend with policy. New York City introduced conversion incentives offering up to a 90% property tax exemption for office-to-residential projects that include at least 25% affordable units. Washington, D.C., went even further, approving a 20-year tax abatement for commercial-to-residential conversions through its Housing in Downtown initiative. These moves show that governments increasingly see reuse not just as a financial tactic, but as a way to answer pressing housing needs.

This is precisely the terrain where Rico Florez's method resonates. For him, adaptive reuse is not yet realized in practice but stands as a central element of The SABI Method. While his remodelings in Bogotá were not adaptive reuse in the strict sense, they taught him the importance of transformation. He now frames adaptive reuse as an unexplored yet essential strategy, one he is preparing to apply in upcoming projects in Miami. By building this commitment into his methodology, he positions himself ahead of the curve, aligning with the very outcomes cities are only beginning to legislate.

These ideas are not abstract for Leonardo. They are embedded in the body of work his firm has produced. Founded in 2011 in Colombia as Rival Arquitectos SAS and later expanded to the U.S. through SABI LLC in Miami, the studio has delivered over 35,000 square meters of residential, commercial, and institutional projects. Among its most recognized works are the UPTC Engineering Labs in Tunja, multifamily housing in Bogotá, and the Shanti School now underway in Miami. This portfolio anchors his vision that architecture can generate social and economic value simultaneously.

Leonardo Rico Florez has demonstrated his approach through remodeling projects in Bogotá. A case in point was the renovation of the Agence Française de Développement (AFD) offices. The original office layout was fragmented, with narrow corridors and limited natural light, undermining the agency's public-facing mission. Leonardo approached the project as a chance to reprogram the space so that its architecture embodied the institution's diplomatic and cultural role. The redesign emphasized openness and circulation, replacing enclosed offices with transparent partitions and creating fluid connections between workspaces and common areas. This made the office area feel less bureaucratic and more like a civic platform, where staff and visitors could experience the agency's values in spatial form.

However new, his residential builds carry the same ethos. In Bogotá's multifamily housing, he designed communal terraces and shared green areas in projects where none had been planned, turning standard apartments into settings that foster community life. In Colombia's Coffee Region, he designed new homes that combined vernacular building traditions with contemporary layouts to ensure that new housing respected local identity while offering modern comfort. Across these projects, construction is treated as an opportunity to create dignity and connection in everyday living.

As Leonardo puts it: "When you reuse a building, you inherit its memory. The challenge is to keep that memory alive while giving it relevance for today. If you succeed, the result is not only efficient. It gives a neighborhood continuity, a sense that the past and present belong to the same story, which is the greatest benefit."

When New Builds Still Matter?

While adaptive reuse is gaining traction, there are still moments when building from scratch is the only answer. New universities, public facilities, or cultural spaces often demand fresh construction—but that doesn't mean abandoning social purpose.

A case in point is the Universidad Pedagógica y Tecnológica de Colombia (UPTC) Engineering Labs in Tunja, Colombia, designed by Leonardo Rico Florez together with his partner, Martha Josefina Valderrama, at SABI. The commission was framed as a purely functional academic building on a modest budget, in a harsh and almost featureless setting. Instead of treating these constraints as limits, he introduced a central plaza that gave the university a civic heart: space for students to meet, orient themselves, and feel ownership beyond the classroom. "The project was never about formality or monumentality," he explains, "It was about giving meaning to structure, letting construction become architecture. The laboratories open toward a central void that organizes life and movement, transforming a purely academic program into a place of encounter. In the end, what remains is not an object, but a place where structure and learning converge." For Rico Florez, the project was proof that scarcity can be turned into an advantage: simplicity made monumental, functionality made humane.

The result is expected to be a building that goes beyond meeting academic needs. It will give the university a civic heart. Projected to be finalized by the end of 2025, the project shows that new construction can still embody the values of inclusion and identity, proving that innovation in design is not about spectacle, but about shaping spaces that serve people.

The Bigger Idea

What unites both adaptive reuse and new construction is a growing belief that architecture should act as more than a backdrop to economic activity. Increasingly, designers and developers see buildings as instruments of social value, shaping how people connect, how they feel about their cities, and even how resilient communities become. This shift moves the conversation away from flashy "starchitecture" toward something more grounded: architecture as service.

Leonardo Rico Florez places this idea at the heart of his work and has structured it into what he calls The SABI Method. The name comes from his practice, the Studio of Architecture and Building Innovation (SABI), which he co-founded in Bogotá before expanding to Miami. Its values: accessibility, contextual awareness, and social impact—are embedded in the method itself.

The framework follows three main steps. First comes diagnosis, looking at the crucial details of a building or site, from its structure and natural light to zoning and neighborhood context. Then comes reprogramming, which is imagining new futures, whether that means turning an office tower into housing or rethinking a public building as a community hub. The final step is value creation, i.e., testing whether the project makes sense financially and socially, by comparing costs, timelines, and potential impact. Traditional development often treats social value as a side effect, something optional if budgets allow. By structuring it into every stage, from the first site survey to the final financial model, the SABI Method builds social outcomes into the base of a project rather than adding them at the end.

For Leonardo, the method is a way of systematizing what he has long practiced: treating financial return and social contribution as two sides of the same equation. "The building is never the protagonist," he says. "The inhabitant is. If the space doesn't improve life, then it's not architecture. It's just construction."

The SABI Method shows that aligning ROI with community outcomes is not utopia, as it's already informing housing and institutional projects in South America (Colombia) and North America (the USA).